Prosaic Times: If you can code well, you can write well – and you must write well

In building a system you traffic in user experience, structure and semantics. These provide the timeless building blocks of good writing.

The break provides me with the opportunity to spend a lot of time hanging out in my favorite coffee shop on first avenue — so this is the communicating with humans issue of Prosaic Times. There’s a piece in the backlog that explains how the polar bears in the Central Park Zoo demonstrate why GenAI can’t write prose for you. The main argument explains that every good software engineer has the potential to be a great writer. The wire section includes an article explaining why we can sense LLM-generated prose when we read it.

From the backlog

The main argument: If you can code well, you can and most write well

I hate the expression “only words.”

“These are the times that try men’s souls.” “Workers of the world unite; you have nothing to lose but your chains.” “We shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be.” Armies march based on only words.

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” Americans prosecuted the Cold War, landed men on the moon and embraced civil rights based on only words.

Technologists dismiss the efficacy of only words compared to code – but that limits their reach and scale. Companies need their best engineers to influence their peers at scale. They need them to advocate for elegant architectures and to explain modern engineering practices.

Yes, you must talk to people – but that is limited in reach and time. You can only influence as many people as you can meet directly and for as long as they remember your point. Sustained influence at scale requires the written word. Ideas you commit to paper can reach thousands of people who will benefit from your insights, sometimes for years.

Technologists lament that they lack the wiring to write well. Nonsense -- in building a system you traffic in user experience, structure and semantics. These provide the timeless building blocks of good writing. What’s more, you can use AI as part of your writing motion no less than you can use AI in your engineering motion.

Be intentional about reader experience

We obsess about user experience in building systems. We want to make it easy for the user to achieve an outcome. This is no less true when we write – we want the reader to learn and we want, in many cases, to inspire the reader to action.

Tie your methods of persuasion to your readers and your objectives

Writing is a political act. You write not merely to inform, but to motivate. Who is your audience and what do you want them to do? What prevents them from taking the action you want them to take? Are they skeptical of your proposed course of action? Or do they just need to understand how to prosecute it? To what extent do you need to convince, or just inform?

Aristotle defined three means of persuasion: ethos (the writer’s credibility), logos (logical explanation) and pathos (appeal to values). Talking about enterprise technology logos will always be central to your writing. But the more you need to motivate, rather than simply explain, you will also draw upon ethos and pathos.

Ethos is dangerous – use it sparingly. Thinkers from Aristotle to John Locke have pointed out that a speaker’s or writer’s credibility only imperfectly predicts the validity of the argument. Even the most brilliant architect sometimes makes a wrong call. That said, ethos is still important, especially when you ground it in process rather than personalities. Readers respond well when writers explain the data collected, analysis performed and experts consulted in formulating an argument.

Pathos is likewise dangerous but valuable. We shouldn’t decide what platforms to use and where to host systems based on emotional arguments – no matter how heated discussions of cloud adoption can get. But values matter. Even the most fastidious engineer is an emotional as well as a rational animal. Invoking values you share with the reader – engineering craft, or the importance resiliency will have for your customers – will enhance the force of your argument.

Tune your content to reader sophistication

Some will urge you to keep it simple – they are foolish, or at least simplistic. You need to understand your audience and tune your content for that audience. Are you writing for finance executives who may not have thought much about software engineering processes? Or for senior architects who cut their teeth debating the efficacy of fourth generation languages?

Providing the definition of the software development lifecycle or data protection reduces your credibility with a technical reader -- they will infer that you are writing for the uninitiated. [This challenge is not unique to technology. My colleague Charlie Barthold likes to recall he wrote an article for the boating column in the New York Times and the editor insisted he explain to readers what an anchor was.]

The Zone of Proximal Development theory indicates people learn from material just outside their comfort zone. Material inside their comfort zone bores them. Material far outside their comfort zone stresses and confuses them. Material just ahead of your intended audience engages the reader without scaring him or her away.

Ideally, you can land your writing right in your audience’s zone of proximal development, but you’d rather be slightly ahead of the reader than slightly behind him or her. Far better for the reader to say, “wait a second – let me read that again” than ask “why am I reading this when there’s nothing new here?”

Maximize insight per page

We write to inform, to tell people something they didn’t know before they opened the document. Ask yourself: What do my readers know? What will they stipulate? What do they need to understand to do their job better? If everybody knows something, you may not need to write it all.

Opinions are cheap; facts are dear. The world is awash with hot takes on how AI will change the world or not. Nobody needs another polemic here. They might, however, benefit from an explanation of an economic analysis of AI use case in your sector or a review of the architectural patterns that allow AI to scale in an enterprise. You should scrutinize every sentence you write, asking yourself: Does the reader know this? Would the reader benefit from knowing this?

Everyone has heard the sentiment “I have written you a long letter because I did not have time to write you a short one.” There is truth here – careful editing will remove ancillary points, eliminate unnecessary words and sharpen ponderous sentences.

But brevity does not equal effectiveness. The Wealth of Nations runs to 800 pages, and Das Kapital is even longer – and both changed the world. Technologists deal with thorny, multi-faceted issues. Describing an actionable cloud strategy for a global behemoth requires more information than will fit on a few pages. Be intentional -- do you need a few pages to support an initial discussion or a detailed compendium that managers can consult repeatedly?

Be specific

Specificity builds credibility. Specificity provides insight to the reader. Specificity is difficult and sometimes scary.

You might write something like “There are opportunities to optimize the change management process.” What does this tell the reader? Almost any process can be improved in some way – the writer hasn’t explained how the change management process compares to similar processes in other companies or what rationale exists for improvement.

You must synthesize for your reader but beware of over-synthesis. Saying “the change management process is not best practice,” elides the questions of what best practice change management looks like and whether it applies in this situation. Far better to say, “The average change request requires 17 different approvals, which take five days to secure” or “There is no standard change process; every request follows the same path, no matter how simple.”

Stories make your points concrete. After you explain that the average change request requires 17 approvals, provide an example of all the hurdles one change request needed to surmount – your readers will remember it.

Sometimes vagueness comes from fear. Writers want to mollify colleagues by avoiding damning facts. Often the reverse is true, as readers interpret a vague statement in the most negative light. Far better to show your work and explain how and why a change request requires 17 approvals. Gutless writing is bad writing.

Lean into structure

Does architecture matter in building systems? Every now and again, I hear some wizened old head say that. That not everyone listens doesn’t make it any less true. Just as systems require architecture, writing requires structure.

Depart from a point of common understanding

I point out above you should never write anything your audience already knows, but there is one exception. Begin with information readers will stipulate to – then explain what you are talking about and why it is important. This reduces reader confusion, increases engagement, establishes credibility, and demonstrates empathy. You can also use context setting to draw readers with different levels of sophistication and different starting points into your argument.

You might start by acknowledging a common understanding that cloud adoption can yield large benefits and that cloud security is one of the biggest barriers to cloud adoption. You’ve quickly set the stage, describing a problem or an issue you propose to address and why you understand that your readers care about it so much. Now pivot to communicating new information grounded in facts.

Say it before you write it

I frittered away some of my college years running a campus daily newspaper – so I occasionally had to edit articles by clueless freshman reporters. One brought me a piece about some campus happening. I called it up on the screen of my Mac SE (with the third-party 68030 processor). It was incomprehensible. If a Henry James novel had sired offspring with a Judith Butler treatise, it would read like that.

I said to the nervous freshman, “Just tell me what happened.”

He was confused. I suspected this was his usual state.

I elaborated: “If you were describing to your roommate what happened, what would you say?”

The freshman then explained to me, in straightforward terms, what happened.

“Good,” I said, “write that,”

Human speech emerged more than 135,000 years ago, and writing maybe 130,000 years later. We are evolutionarily wired to tell each other stories verbally. Build on that.

I also use visualization frequently when I write. Visualization is the process of picturing yourself completing a task. Basketball players visualize making a free throw. When I write a document, I imagine myself explaining it to a member of the audience. What are the salient points? How would I frame the argument? I use what I visualize myself saying to structure the sequence of passages I write.

Use the Pyramid Principle

I think every new McKinsey associate gets a copy of Barbara Minto’s Pyramid Principle. The book’s prescription is simple and demanding -- figure out your main point, decompose it into a few supporting points, then decompose those into supporting points. Continue that all the way down the chain until you get to the supporting data. Then turn your “pyramid” into an outline and ultimately a draft.

Also, map your executive summary and your table of contents (or tracker) together on a point-by-point basis. Too often I read an executive summary and then turn the page to see the table of contents of tracker using a different structure, which is bewildering. If you have five points in your executive summary, you should have five chapters in your table of contents or tracker. This will allow the reader to follow your argument point-by-point – and to skip past points he or she will stipulate to the sections requiring careful study.

Write with verve

Nobody wants to deal with messy code. Nobody wants to read inelegant prose. Careful sentence construction and vivid word choice make reading less of a chore – so your readers will more likely understand, remember and act on what you write.

Make your sentences forceful

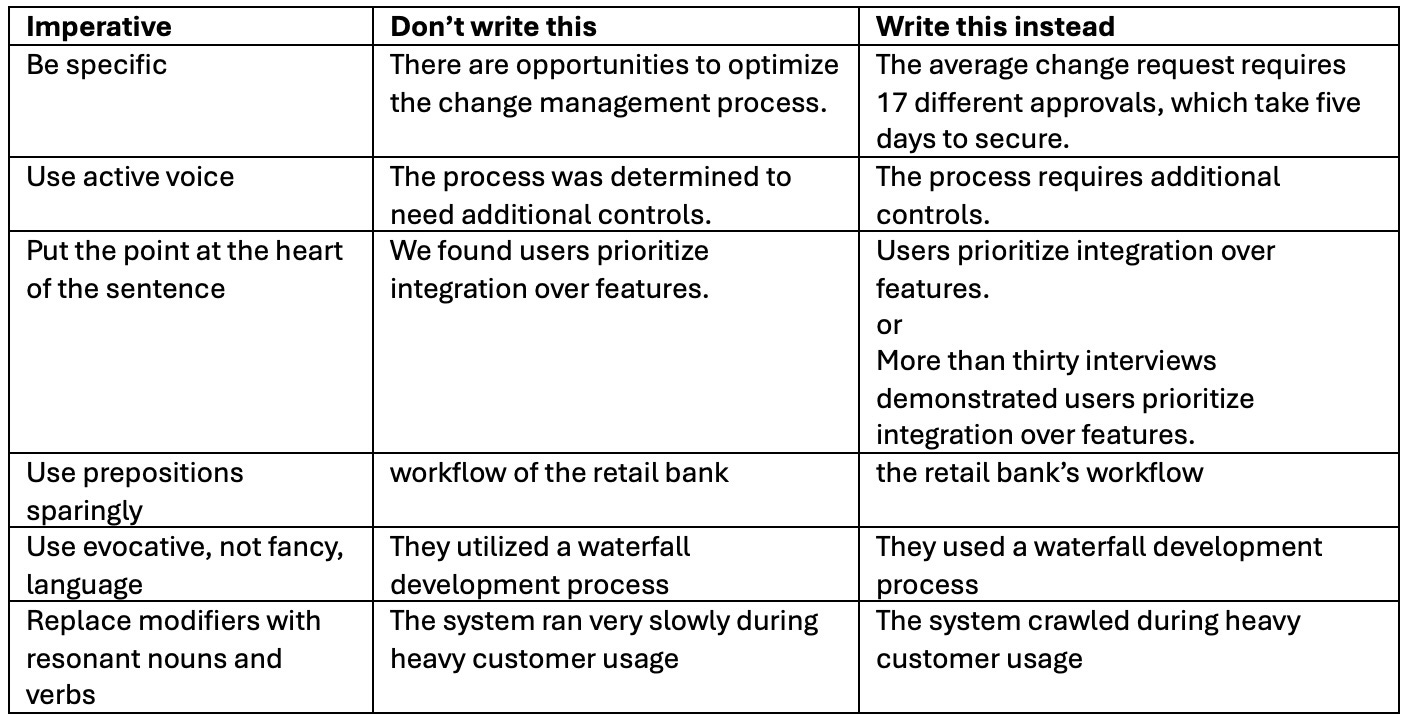

You want to make your sentences feel energetic and evocative – and pull the reader along with your argument. Here’s how you do that:

· Use active voice. Take the sentence “the process was determined to need additional controls.” Who determined the process needed additional controls? Elves? A family of intelligent otters? The subject and verb stand at the center of the sentence: “Workers of the world unite.” Who is important here? Workers. What should they do? Unite.

· Put the point at the heart of the sentence. People love to write sentences like “We found users prioritize integration over features.” Your finding is superfluous – if you didn’t find it, why would you write it? Instead write “Users prioritize integration over features” or “More than thirty interviews demonstrated users prioritize integration over features.”

· Use prepositional phrases sparingly: Prepositional phrases make sentences longer and more complex. In place of “stronghold of waterfall development,” write “waterfall development stronghold.” In place of “workflow of the retail bank,” write “the retail bank’s workflow”

· Vary sentence length and complexity. After a couple of longer sentences with dependent clauses, hit the reader between the eyes with a two- or three-word sentence to emphasize a point.

Use word choice for impact and precision

English is a mongrel, the issue of first Germanic and Norman invasions of the British Isles – and then the British Empire’s encounter with the rest of the world. It has more than 170,000 words in active use, well more than in French, Spanish, Mandarin or Japanese. Here’s how you might employ them forcefully:

Use evocative, but not fancy, language: Use words that give readers the texture and flavor of your point – for example: “The retail business unit is a waterfall development stronghold.” In contrast, writing “utilize” when you mean “use” provides no more texture, even with the additional letters.

Replace modifiers with resonant nouns and verbs: The noun and the verb power a sentence. Modifiers like “critical” or “significantly” only clutter up your writing. Don’t say the system ran very slowly. Say it crawled.

Use terms of art but not jargon: Technical terms specific to a community convey much information in few words. Peers will know what “standard change” or “full-stack developer” means. Nobody agrees what “governance” or “alignment” mean. Either avoid or define your terms so the reader understands what you mean.

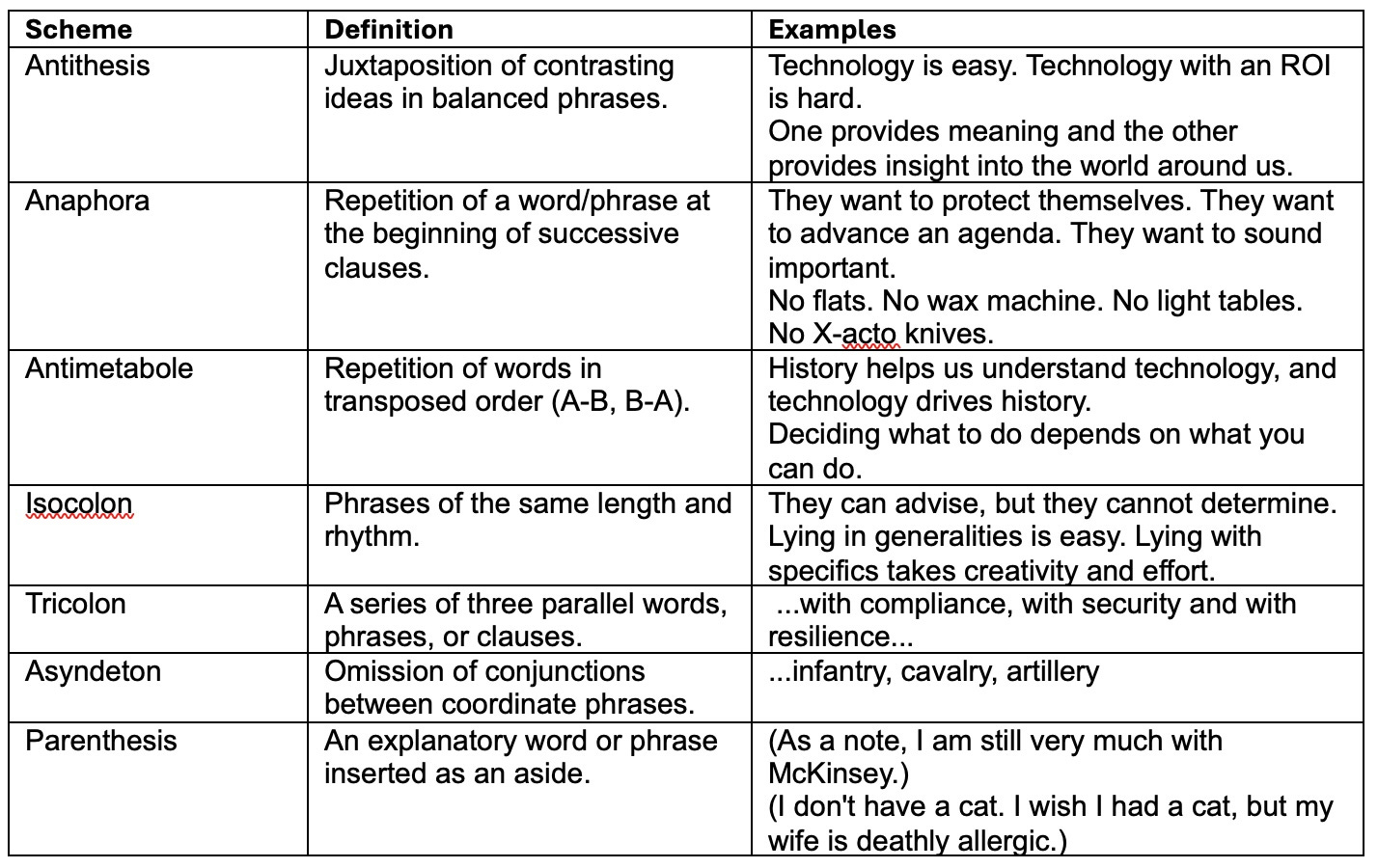

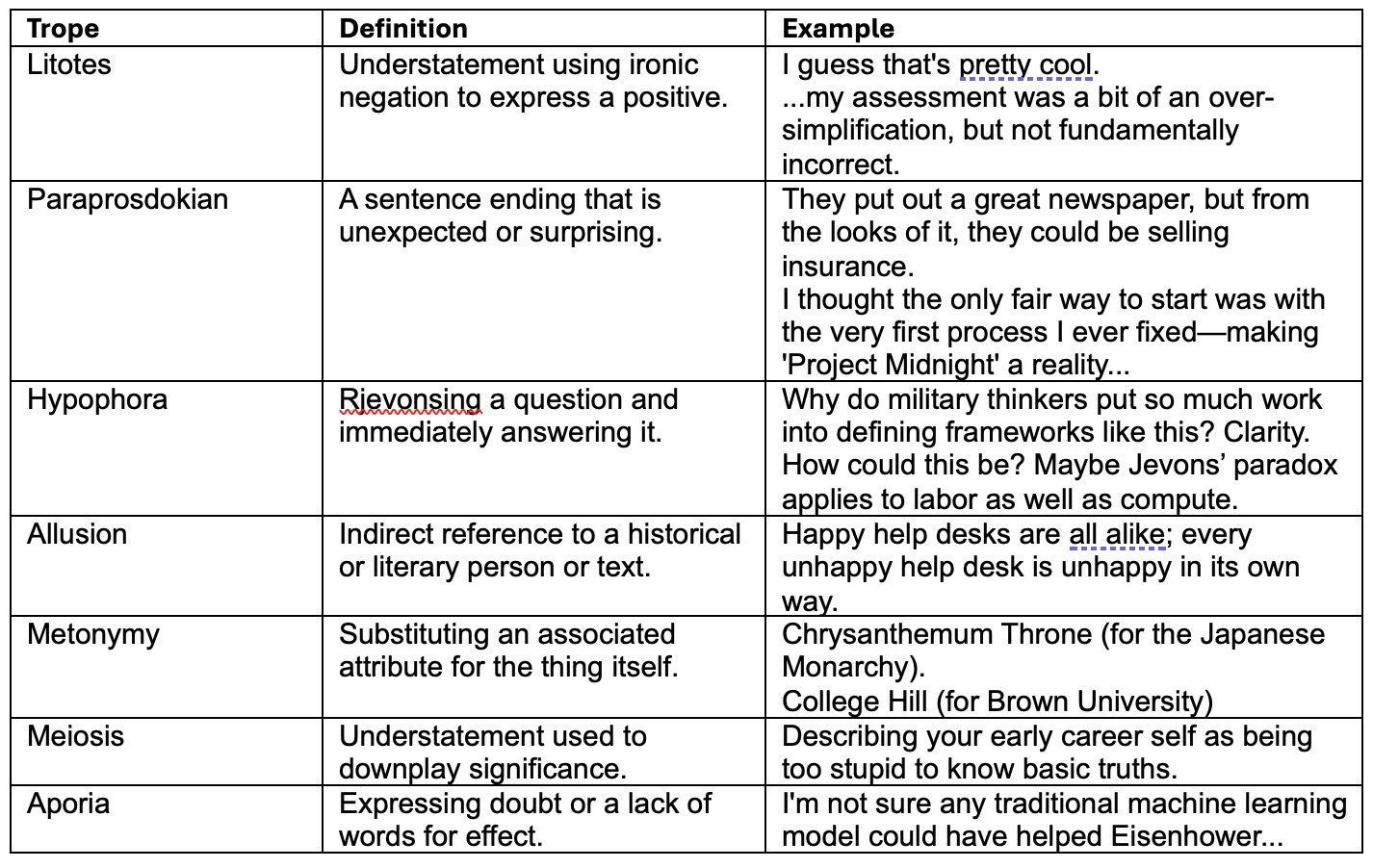

Tap the wisdom of the ancients

The practice of rhetoric is very old – writers have sought to persuade readers for millennia. Roman rhetorician Quintilian laid out a system of schemes and tropes in writing. Schemes are patterns for arranging words and tropes are semantic practices for using words figuratively. Both make your writing more memorable and emotionally resonant because they draw on how we speak. I use some of them all the time, and asked Gemini to scan Prosaic Times for examples.

Build GenAI into your writing motion

Perhaps you’ve thought about how AI might transform software engineering and other enterprise technology domains? Maybe a little bit? GenAI can change your writing motion no less than it can change your coding motion. That doesn’t mean AI can write for you, at least if you want to avoid torturing your readers.

Prose from an LLM has a flat, almost plasticky feeling. I’ve written tens of thousands of words for the “Tech Office Update” (distributed inside McKinsey) over the past 18 months, never relying on an LLM to generate text. For one issue, I prompted an LLM to write two sentences describing the Palatino and Franklin Gothic typefaces. Within twenty minutes of hitting send, a colleague emailed to say I clearly didn’t write those two sentences. Your readers can tell. Here’s how you can leverage GenAI well:

Use GenAI to red-team your thinking

Writing is scary. Conscientious writers always ask themselves, “Did I get this right?” I use a few prompts to use GenAI to test the originality and validity of my thinking:

· Is it valid to say <proposition>?

· Has anyone made the argument <proposition> before?

· If someone were to make the argument against <proposition> what would they say?

Use GenAI for motivation

Writing is lonely – you sit typing at your computer. People have other things going on in their lives – they can’t often take time to review your draft and provide thoughtful input. I find the opportunity to finish a section, put it into a chat interface, an incentive to keep writing – even if it does sometimes lead to an extended argument between me, Gemini, ChatGPT or Grok.

Use GenAI to contain your bad writing habits

I can be discursive – sometimes telling a story matters more to me than getting to the point. This drives ChatGPT, in particular, metaphorically nuts, so it will push to cut out extraneous detail, get to the point more quickly and make sure I signpost my structure.

English is no less code than Python or Java – middle schoolers used to learn to diagram sentences. You can ask your favorite model to diagram the sentences in your prose – see how complex or repetitive your writing may be.

I must ignore some of its advice. It always tells me to be more explicit with some points -- I can’t do that. You don’t want to place too much cognitive load on the reader, but you also want to make the reader work for it a bit.

Technologists can be good writers. Bloody hell, sometimes technologists are exceptional writers – ones whose writing moves us all to think and act in different ways.

The Cathedral and the Bazaar, by open-source legend Eric S. Raymond

The Mythical Man-Month, by Fred Brooks, who managed development for the IBM System/360 mainframe

The Phoenix Project, by Gene Kim (even if it’s a homage to The Goal by Eliyahu Goldratt)

Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software, by Charles Petzold, who is one of Microsoft’s seven “Windows Pioneers”

They should be inspirations to us all!

The wire section: what I’m reading, watching and listening to

Stylometric comparisons of human versus AI-generated creative writing, Nature

University College Cork (UCC) researchers used literary stylometry, computational methods traditionally used to identify authorship, to examine LLM-generated prose.

Yes, AI generates fluent prose, but writes in a narrow register. Human-written prose feels human because it draws on human experience — resulting a far-wider stylistic range

Guardians of the Agents, Communications of the ACM

A new article published in Communications of the ACM suggests that companies should adopt, in effect, an analogue to Cloud Security Posture Management (CSPM) for agents

Current agentic security methods have shortcomings -- guardrails create false positives, repeated confirmations degrade the UX and there’s the risk of prompt injection

The article proposes forcing the agent to generate a plan when calling tools and then programmatically evaluating the plan in terms of security policies

Some professional writers are resisting AI, but others are building it into their personal writing motion. Whom do you think will win here?

The Race to Build the World’s Best Friend, The New York Times

I’m sure most people have read the NY Times article about frontier labs’ chat interface development. One detail struck me – how labs are using chat histories to train their models: “As ChatGPT swelled to serve hundreds of millions of users, the collective chat histories became by far the largest database of human-A.I. interaction in history. The OpenAI researcher Christina Kim calls this the ‘data flywheel.’”

I suppose this is part of a secular shift in labs moving from just hoovering up all the legally available text on the web to training (in different ways) on specialized data sets. Expert generated text seems to be increasingly important here. Maybe all the Ph.D. candidates who won’t become professors as fewer students enroll in college will get work generating text for frontier labs?