Prosaic Times: The tyranny of the use case and the need for enterprise tech doctrine

The “we need better technology strategy” issue

This issue looks at technology strategy and how we make it better and more applicable.

From the backlog: when technology investment create value, why platforms are so important and how strategy pervades everything we do, even parenting

The main argument: Learnings from military strategy offer insights that will lead to better enterprise technology strategy — and better returns from technology expenditures

What I’m reading reading, watching and listening to: A book about the history of the software industry illustrates the eternal nature of some technology strategy challenges

From the backlog

Here’s a few items from the backlog relevant to the theme of this week’s issue:

Stop typing. Go square dancing. Then we’ll code. Or why thinking platform is so important.

Nobody should raise kids without taking a class in game theory

The main argument: Learning from military strategy in development better strategy models for IT

It was 2003. A senior partner had invited me to dinner at Oscar’s Brasserie at the Waldorf Astoria to discuss a white paper I had written. We both wore suits and ties. So did most of the patrons. The restaurant provided those flat, blunt special fish knives for our seafood dishes. It was a different New York.

“So tell me this,” my colleague demanded, “is there really such a thing as infrastructure strategy? Isn’t it just managing a bunch of servers?”

If I had been more confident and better-read I might have shot back, “If you tell me this: was the ‘left hook’ strategy General Norman Schwarzkopf deployed in the First Gulf War just driving a bunch of tanks around?” But I wasn’t so I didn’t.

If someone asked me this question today I would mention Sir Lawrence Freedman’s magisterial history of the idea of strategy. In addition to Clausewitz, Mahan, Jomini and Mackinder, Freedman discusses all sorts of personalities — revolutionaries and political activists like Bakunin and Mario Savio — you would not expect to see in a book about strategy. Freedman’s point? Any time you seek to achieve an objective in a dynamic environment with constrained resources you are doing strategy. So, to my colleague: no we’re not talking about just managing a bunch of servers.

So what does strategy mean for an enterprise technology function? How should a CIO or CTO think about strategy? Here’s what you should take away from this piece

The history of writing about IT strategy isn’t especially helpful — enterprise technology is too new a domain and has evolved too quickly over the past several decades

Military strategy provides some insights — create an ontology for strategic layers, avoid unidirectional thinking, use learning to mediate between deliberate and emergent strategy and think in terms of dynamic systems — mostly not applied in enterprise technology

CIOs and CTOs can apply these learnings in two ways — end the tyranny of the use case in business-technology strategy and use doctrine to reshape how they run their own function

Management teams face a choice — as we enter the age of AI, they can either sustain the insufficient strategic models for technology of the past, or they banish siloed thinking and multiply the economic value they get from their technology investments

What is IT strategy? It’s not clear, and the 1970s provide no answers

Because I’m just that cool, I’ve been reading about this history of IT strategy and I stumbled on Richard Nolan’s stages of growth framework developed way back in the groovy 1970s, when I was still watching “The Electric Company” on Channel 13.

Nolan’s first iteration of the model suggested four stages of IT adoption

1. Initiation — only the very savvy have even heard of a given technology

2. Contagion — proliferation of applications, rapid budget growth

3. Control — reaction to cost increases, centralization and demand management

4. Integration — more professional management, integration across systems, return to growth in demands

At first, I wanted to make fun of this, but it describes an important strategic issue that CIOs and CTOs must address. Vendors introduce a new technology. Business users get excited about it, and demand its implementation as quickly as possible. Spending increases, sometimes via shadow or quasi-shadow IT. The CFO gets annoyed. The CIO and CTO try to consolidate the mess that has been created. And then the cycle repeats. You might describe this as an “IT doom loop” that accretes technical debt, with all its baleful impact on agility, cost and risk.

Nolan added two phases in the late 1970s. They were so hard to figure out I won’t even mention them here. Waiting to buy gas for your El Camino while listening to The Bee Gees on the 8-track was probably not conducive to rigorous thought on technology strategy. And it’s not clear to me that the enterprise technology world has gotten more rigorous about what it means by strategy since then.

Military strategy provides at least some insight

Thoughtful individuals have been thinking about national strategy and military strategy for much longer than they have been thinking about business strategy or enterprise technology strategy. From their thinking, CIOs and CTOs can derive three imperatives: for on ontology of strategy, for integrative thinking, and for a balance between deliberate and emergent strategy.

The ontology of strategy

NATO defines four levels of conflict:

Grand strategy: The coordination of all national resources (diplomatic, economic, military) to achieve a political objective. During the First Gulf War the United States pursued a grand strategy, laid out in the Carter Doctrine, of preventing any power from dominating the Persian Gulf.

Military strategy: How a country will use armed forces to support political objectives. In 1991, allied armed forces aimed to not only eject Iraq from Kuwait but also destroy the Republican Guard, but not necessarily remove Saddam Hussein from power.

Operational art: Schwarzkopf directed 250,000 troops to maneuver west, then north and east so they could attack the Republican Guard from the flank and rear, rather than head-on.

Tactics: Hundreds of local decisions by field and company officers — for example the decisions made by then-Captain H.R. McMaster in attacking Iraqi tanks in the Battle of 73 Easting.

Why do military thinkers put so much work into defining frameworks like this? Clarity. Different levels of staff (theater, division, company) understand what level of planning they are responsible for and what decisions they must make.

In contrast, how many times have you sat in a conference room listening to someone talk about IT strategy or technology strategy, not having the foggiest idea what that person was talking about?

Sometimes IT strategy refers to what business capabilities IT will provide to the business — which processes to digitize, what type of analytics to support? Naturally, this raises the question of whether you can even do IT strategy across a big complicated, multiline enterprise — or do you have to do it at the business unit level to be meaningful?

Sometimes IT strategy refers to how IT should run itself as a function. Should it be consolidated or decentralized? How standardized should it? Should it adopt a product operating model? Quite often, CIOs frame IT strategy this way because business leaders say “I’ll tell you what to build. You just worry about building it as quickly and cheaply as you can.”

Avoid unidirectional thinking

While the NATO strategy “stack” may be a hierarchy, it’s not supposed to be a unidirectional one. Concepts developed at lower levels of the stack may outlive grand strategies — or may create options that shape military strategy or even grand strategy. The Pentagon created AirLand Battle doctrine to improve its operational art in supporting the grand strategy of deterring or, if need be, repelling a Soviet attack on Western Europe. Mercifully allied forces never had to use this doctrine in Europe — but they translated into a completely different grand strategic contest in 1991, when it underpinned the “left hook” that Swarzkopf used to outmaneuver and destroy the Iraqi Republican Guard.

Better operational art (and better doctrine for operational art) also creates grand strategic and strategic options for commanders to consider. Archers’ proficiency with the longbow didn’t just win battles for the English in the Hundred Years’ War — it allowed Edward III and Henry V to shift their grand strategy from protecting their holdings on the continent to contesting the French crown. Until, of course, the French trumped the longbow at the Battle of Castillon in 1453 with the introduction of artillery. Centuries further into the millennium-long contest between England and France, the Jack Tar’s better gunnery technique created better strategic options for Admiral Horatio Nelson, especially at the Battle of Trafalgar.

How much unidirectional thinking do we see about enterprise technology in large enterprises. How often do business leaders really think about how new technologies create options for them that they could not previously have considered. The very word enablement implies unidirectional thinking — that somebody comes up with a business strategy and technology enables it.

Use learning to mediate between deliberate and emergent strategy

For much of the Great War, each side preceded massive attacks with massive artillery bombardments that both warned defenders of an imminent attack and chewed up the ground in no-man’s land, slowing down troopers charging into machine gun fire. This was a very deliberate strategy. The result? General Robert Nivelle’s offensive in 1917 yielded minimal gains at a cost of 187,000 casualties over a few days. The British Empire suffered 275,000 casualties the same year at Passchendaele in return for a few miles of ground that the Wehrmacht shortly recovered.

By 1918, both sides in the war discovered infiltration tactics. Rather than assuming they know a priori where to make a major attack, they would probe the enemy line for weak points (sometimes located at the juncture between two formations) and reinforce success.

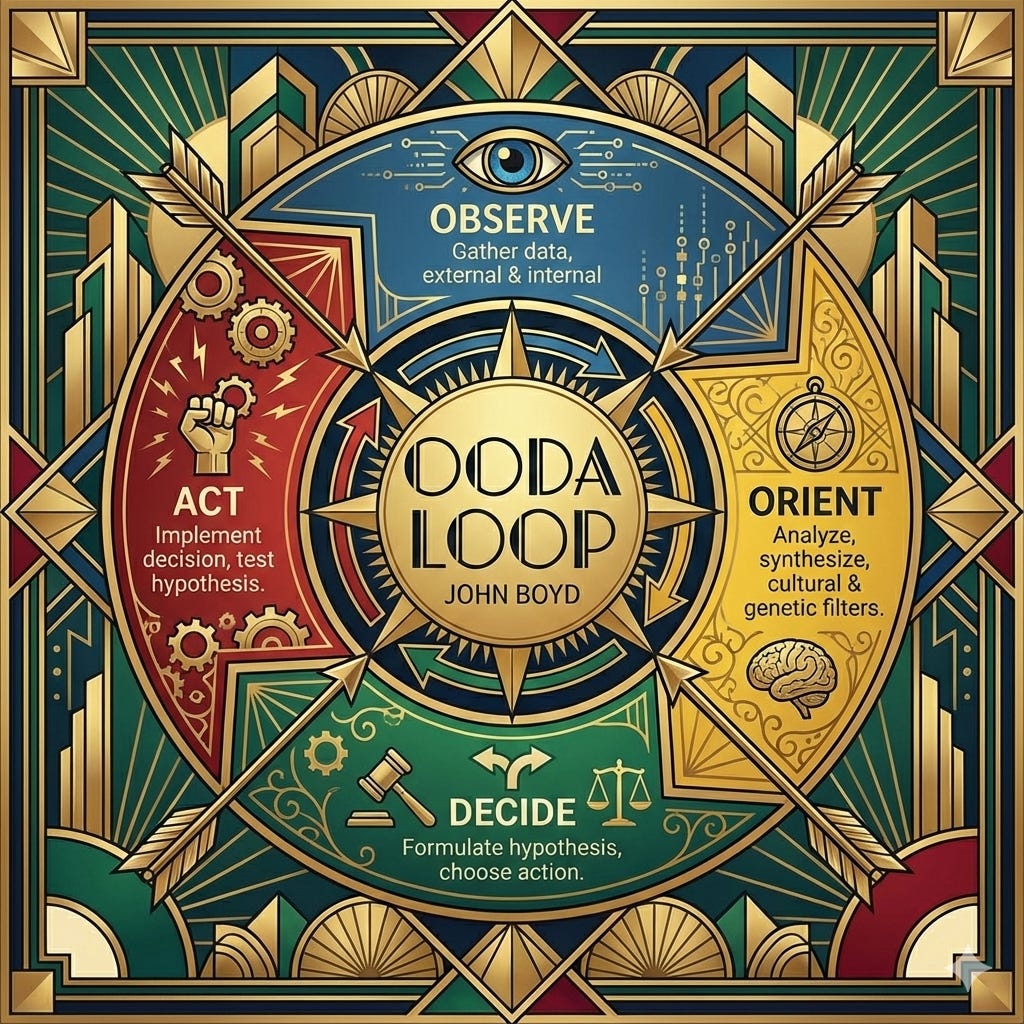

Colonel John Boyd’s Observe-Oriented-Decide-Act (OODA) loop is a model of how people and institutions make better decisions through recursive learning in competitive games. It provides a mechanism for balancing deliberate and emergent strategies, which emerge from the bottom up:

Observe: gathering data about the external environment and internal system — including information about the enemy, the physical surroundings, and unfolding circumstances.

Orient: interpreting and synthesizing observations through filters such as institutional objectives, higher level strategies, culture, prior experience to form a mental model of the situation

Decide: selecting a course of action based on the current orientation — choosing from competing hypotheses or possible responses

Act: taking action that alters the environment, producing new data for the next set of observations

The implication? There is a dialectic between deliberate and emergent strategy. The deliberate strategy is the hypothesis that the OODA loop tests. It allows for local experimentation and innovation that, when successful, can help create refined deliberate strategies. Everything is test and learn.

Of course deliberate strategy sounds quite a bit like waterfall development. In Adaptative Software Development, one of the 17 signers of the Agile Manifesto, Jim Highsmith, described the alignment between the OODA loop and agile: “Boyd’s OODA loop (Observe–Orient–Decide–Act) describes the agile process perfectly. Rapid cycles of planning, acting, and learning allow organizations to adapt faster than their competitors.” Waterfall development required long lags between observing, orienting, deciding and acting – with no feedback loops until the next release, which might only follow years later. Agile development created shorter cycles of information collection, decision-making and execution, with the learnings from each sprint shaping decisions in subsequent sprints.

Too much emergent technology strategy, rather than too much deliberate strategy, may be the more common failure mode for companies. They have dozens of different projects to implement dozens of different use cases that may not be connected to a larger vision how to create economic value.

Think in dynamic systems

A dynamic system is a set of interconnected things (people, groups, equipment) that produce their own behavior over time because of the way they reinforce or influence each other.

Military planners must think in terms of systems. Military forces use doctrine to encourage thinking in systems. Stephen Biddle explains officers must see enemy and friendly forces as interlocking systems of capabilities. Victory in battle depends not on greatest mass or the most cutting-edge weaponry, but on the ability to integrate fighters and weapons into the “modern system of force employment.” The Royal Air Force “Dowding System” in the Battle of Britain provides a great example of a military force using doctrine to use systems thinking to achieve advantage – it fused the use of radar into an integrated system that created intelligence and directed fighter plans to where they would be most effective.

For large institutions, enterprise technology is a complex, dynamic undertaking. It can involve billions of dollars in operating expenses, tens of thousands of employees, hundreds of projects, thousands of applications, petabytes of data and hundreds of thousands of servers. No group of executives can marshal those resources without an effective, fully deployed doctrine.

But most institutions lack doctrine for enterprise technology. They have a high-level strategy that states they will improve efficiency and be responsive to business demands, but they manage technology as a collection of fiefdoms looking after different groups of assets or performing different activities. Others use an information technology infrastructure library, or ITIL, but while that might have been an effective organizing construct 15 years ago, it’s less relevant today, with ITIL focusing on fulfilling requests efficiently, rather than building the scalable platforms businesses require. Many companies have started to adopt product operating models for technology, if only incompletely. This is a great step, but an insufficient one to capture the full value of their enterprise technology deployments.

So how do CIOs and CTO apply lessons from military strategy?

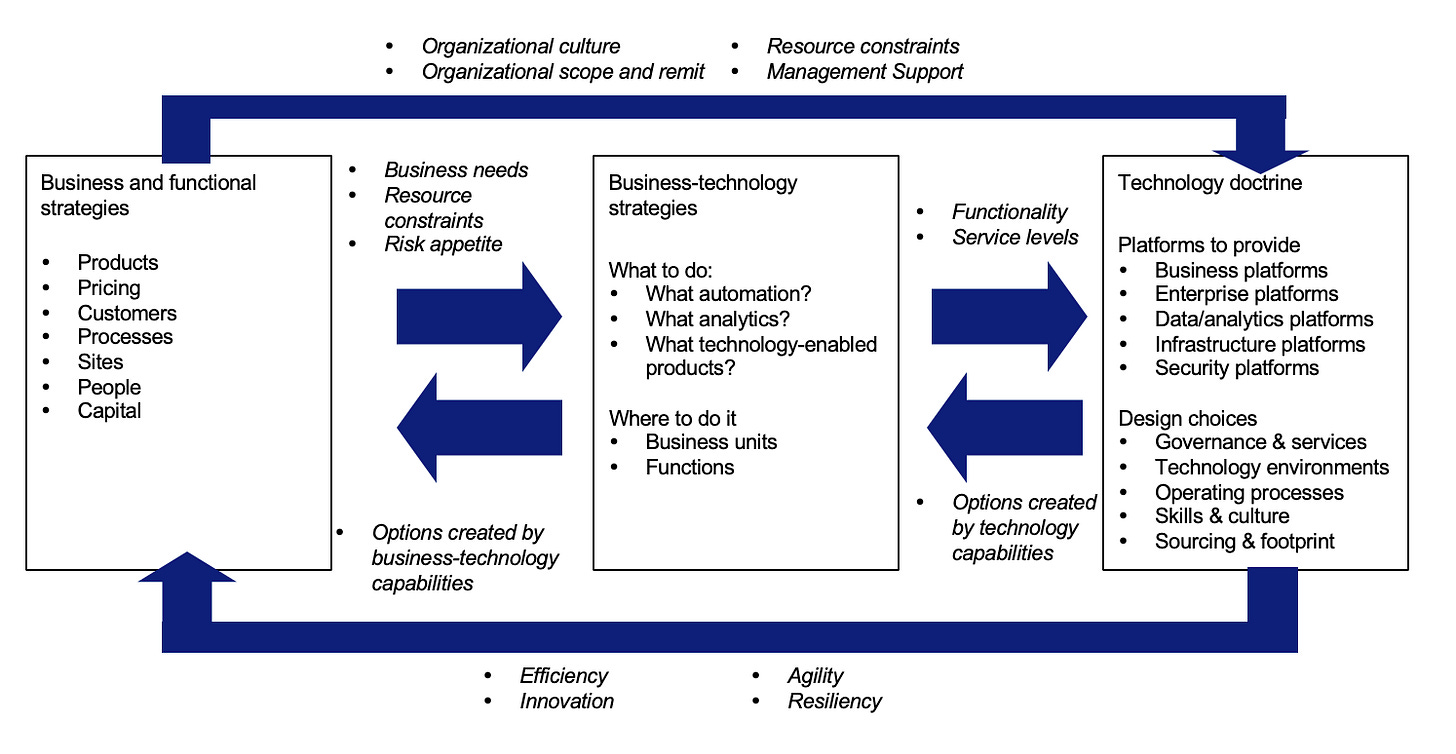

Running a enterprise technology is less complicated (and potentially less expensive) than running a war. CIOs and CTOs can think about two levels of IT strategy: business-technology strategy, which articulates how companies will use technology to create value and technology doctrine, which articulates how they will operate enterprise technology.

Business and functional strategy (i.e. products, pricing, customers, processes, sites, people, capital) are the context

Business and functional strategies shape business-technology strategies (what automation? what analytics, what tech-enabled products?)

Business-technology strategies influence business and functional strategies by creating options for things you couldn’t do (or do economically) before

Business-technology strategies shape (via functional and service level requirements) technology doctrine (platforms, governance, architectures, operating processes, skills & culture, sourcing and footprint)

There are two imperatives here: end the tyranny of the use case in support business strategies and use doctrine to reshape how they run their own function.

End the tyranny of the use case

The use case has been an incredibly important and powerful in the maturation of enterprise technology. It focused requirements definition, and therefore software engineering, on how customers and employees might use an application. It is a form of systems thinking in that sees the user, the application and all the underlying technology infrastructure as a single system.

But all concepts have their limitations. Lower level business managers often see their use case as an end in and of itself, rather than part of a broader undertaking of digitizing the entire enterprise or large pieces of it. In terms of business strategy, it’s like trying to get to the moon by climbing a tall tree. The first 30 feet feel like great progress.

Naturally, the politics here are complicated — many institutions have created robust incentives for managers to engage in siloed thinking. But CIOs and CTOs — with the mandate to think about technology across the entire institution — have an important role to play in making the case for thinking more broadly. How can companies interconnect use cases to achieve a step-change improvement in operational efficiency or customer impact in entire domains?

Corporations are no less dynamic systems than military formations. Markets are no less dynamic systems than military conflicts. Last week I talked about knowledge graphs in the context of agentic memory. Knowledge graphs, with their nodes and their edges representing how nodes can affect each other, do a wonderful job representing dynamic systems. Technology functions can build graphs that model how their companies work — and how they interact in commercial markets — to make the economic case for end the tyranny of the use case and taking a most systematic approach to creating value from technology investments.

Imagine a distribution company. Customers, products carried, orders, warehouses, trucks, drivers and vendors might all be nodes in the graph with edges describing the relationships between them. You could use a graph like this to model the aggregate impact of applying AI across your supply chain. How would being able to track trucks in real time, reroute shipments and charge premiums for tighter delivery windows affect the economics of the company as whole?

Create a doctrine for running enterprise technology

Many companies I know of struggle under a morass of technical debt because, as Nolan predicted, they implemented past innovation in disparate ways with little thought given to how they might run in a consistent, scalable, efficient and safe way over time.

Many companies I know of appear dead set on compounding this problem. They are implementing AI use cases on fragile technology stacks, with little thought given to underlying platforms or sustainable operating models.

Large, born-digital technology companies are different. They have probably gone the furthest in fusing a product operating model, DevSecOps, platform engineering, and sophisticated technology strategies into a doctrine for enterprise technology.

One born-digital company requires all its engineers to pass a six-week “technology university.” They learn that company’s methodology and tools for engineering a new feature, promoting a change into production and fixing a bug. Everyone understands all the components of the system. Everyone understands the common way to achieve repeatable tasks.

At another born digital company the product operating model treats everything (including security and compliance) as a product. As one manager there explained: “There’s no conceptual difference between a request for 50 engineers to develop the next Instagram feature and a request for 50 engineers to work on privacy infrastructure.”

A third born digital company demonstrates how platform engineering, especially when combined with software-defined infrastructure, becomes a force multiplier. More than a decade ago, it embarked on a journey to treat its networking and data center infrastructure as code. This allowed it to scale at unprecedented levels, supporting dozens of complex services.

A few months ago some colleagues and I published an article articulating a potential technology doctrine for large companies based on interviews with more than 100 CIOs and CTOs. The opportunity is very different that it would have been even a couple of years ago because AI, properly applied, allows companies who think and execute systematically, to make a step-change improvement in software engineering productivity and to remediate technical debt less expensively. The result? A multiple in technology returns if they invest in implementing a technology doctrine because they can in a few years shift resources from keeping the lights on to business functionality and because they will get more from each dollar spent on new functionality.

The choice in front of management teams

There is a glaring disconnect between the opportunities AI creates and the strategies companies use for creating economic value from technology. CIOs, CTOs, and their peers across the management have a choice. They can continue to use the lacking strategic models of the past or they can learn from other domains and get much more from the resources they devote to enterprise technology.

What I’m reading reading, watching and listening to

From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry

Is information maybe a shaping factor in our world? Yes I have given academic historians grief about how little the field publishes on this topic compared to others. As noted previously, yes I am a lot of fun at cocktail parties.

Still, lets appreciate this book. I’m still only up to the 1960s — but still amused at how little has changed in many ways.

“For example, after General Electric’s Appliances Division acquired a Univac computer, in January 1954, it took nearly 2 years to get a set of basic accounting applications working satisfactorily, one entire programming group having been fired in the process.”

“According to a joke of the day, ‘there were 17 customers with 701s and 18 different assembly programs.’”

“…promised a system that would generate code 90 percent as good as the code that could be produced by a human programmer.”

“Though SABRE did not become fully operational until 1964, it was of more than 10 years of planning, technical assessment, and system building.”

“The airline’s president, C.R. Smith, remarked “You’d better make those black boxes do the job, because I could buy five or six Boeing 70&s for the same capital expenditure.”

“SACCs was completed with far fewer human resources [than SAGE], owing mainly to the development of JOVIAL, a comand-and-control programming language.”

“During the 1960s, managing software projects was something of a black art.” [Some might argue they it still is — Ed.]

Also many appearances by former IBM CEO Thomas J. Watson, Jr. (Brown class of 1937) who once chastised me: “Young man, there was a time when journalists did not call people during the dinner hour.”

Agent Engineering: A New Discipline

LangChain proposes agent engineering as a distinct discipline from software engineering — that building a non-deterministic product requires a different set of practices. Let’s put aside jokes about how software I wrote in my 20s might have felt non-deterministic — you can legitimately ask how much of the productivity benefits of agentic development we’ll have to give back in testing and tuning.

The Great Partnership: Science Religion, and the Search for Meaning

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks argues that religion and science complement each other, in that one provides meaning and the other provides insight into the world around us. That makes sense, and you can (on good days) lump the the social sciences in with physical, natural and applied sciences, at least in intention. But where do the humanities go? Is history provide insight or meaning? And then where do you put the arts? I had an interesting discussion with a Brown professor Friday about how you thought about the intersection of the arts and epistemology — it puzzled us both.

This article comes at the perfect time, really! Your point about military strategy for tech stratagy is brilliant. Makes me wonder if the human element needs a bit more agile thinking, ya know?