The First Thing I Ever Fixed

In 1991 I accidentally ran a Theory-of-Constraints experiment with X-Acto knives and a waxer. Thirty-four years later every company I advise is making the exact same mistake.

For years I’ve been sending a peculiar Sunday email to a few hundred (now a few thousand) McKinsey colleagues. It contains whatever I happened to read that week, a half-remembered war story, the occasional otter, and a running argument with myself (and others) about technology, productivity, and other things I contemplated sitting in the coffee shope on first avenue.

People kept forwarding it. Eventually someone said, “Just put it on Substack already.”

So I did.

You’ll get one letter most weeks, usually written on Sunday night. It’ll stay free for the first month or so while I figure out what I’m doing. After that I’ll add a paid tier for the occasional deeper piece, live Q&As, and whatever else feels worth paying for.

Yes, I’m still at McKinsey. Views my own, etc.

I thought the only fair way to start was with the very first process I ever fixed—making “Project Midnight” a reality at the Brown Daily Herald in 1991.

It was a good lesson — getting there required synchronizing product and operations with the technical realities of the day. Maybe it was my first experience with systems thinking. Even if I hadn’t read “The Goal” yet and had never heard of “The Theory of Constraints.”

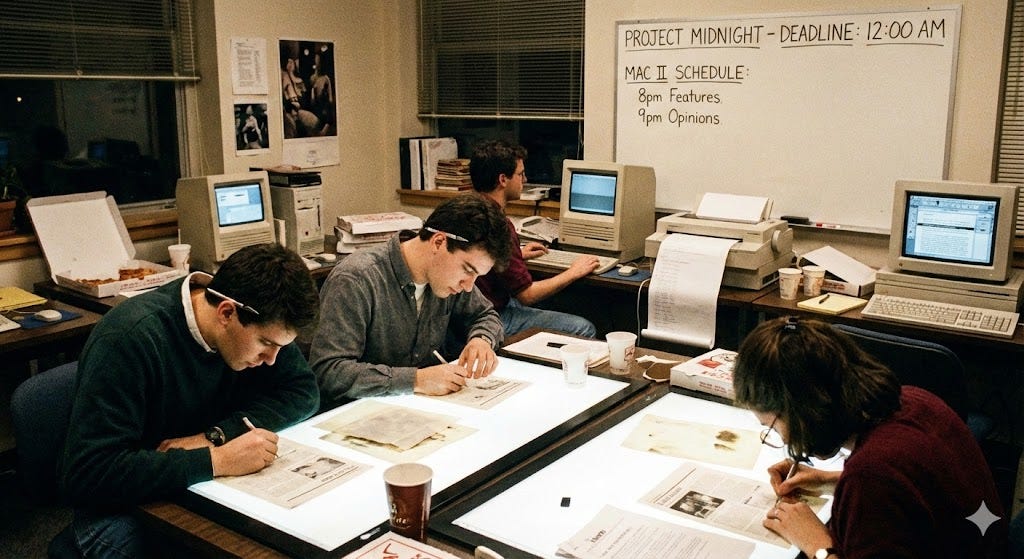

The paper published a print edition every day of the academic year, so dozens of students stayed at 195 Angell Street until the wee hours of the morning from Sunday to Thursday. We used Microsoft Word and Aldus Pagemaker to get the paper pasted down and ready for Cliff to take it to the printer.

The Herald was very advanced in desktop publishing in that era, thanks to David Temkin, but still was quite an analog affair in some respects. A tabloid-format, 600 dpi printer would have been $17,000, so we had to use X-acto knives and a waxer to paste printouts and photostats onto flats. I spent a year with an X-acto knife tucked behind my right ear. Adam Braff was scared of the waxer. I can show you how to toss someone across the room and X-acto safely if you like.

Under the name Project Midnight, years of editorial boards had sought to put the paper to bed before the early hours of the morning. They never succeeded. To my knowledge, not one issue had ever gone to bed before midnight.

When the outgoing board named me editor-in-chief, I reasoned we had to get Project Midnight right. Getting people back to their dorms earlier would reduce the risk that parents would pressure their offspring to quit the paper. And it would reduce the risk that I would fail any classes.

The very first night of the semester we finished the paper at 12:13 am (Amy likes to point out I can remember anything except people’s names.) How did we do this?

< 1 > Design for operations. Most of you have probably never upgraded the memory on a Mac II or Mac IIcx. Adding SIMM cards to a Mac II was a giant pain in the neck — you had to remove the hard drive to get to the slots. Adding memory to the Mac IIcx was a snap — somebody sat down and asked: how do we make this easier?

What, we wondered, if we applied the same discipline to the “product,” the design of the newspaper. So we removed any design flourishes that didn’t make the paper more readable and we tried to pre-build as much as we could in the PageMaker templates we used. For example we dramatically simplified the little element that says “continued on page x,” using a text box property rather than a separate element to display a little line. This eliminated a mouse action. Small in itself, but a dozen of these simplifications, multiplied by dozens of times per issue, added up.

< 2 > Assign property rights. We used Mac Pluses with 16-bit processors and tiny screens to write and edit stories. We used our three Mac IIs with 32-bit processors and big screens to do layout in PageMaker. The Mac IIs were the bottleneck in the whole process — always the night editor, the wire editor, the sports editor, the opinions editor and so forth jostled for time on one of the Mac IIs. There was always nobody using them early in the evening and a line of editors waiting around at 11 pm.

Having read about Ronald Coase’s paper “The Problem of Social Cost” in a “Law and Economics” class, I decided to create a schedule. National news (off the AP wire) and the features section got 8 pm slots. Opinions got a 9 pm slot. News and sports got the 10 pm slots, given that currency was more important for those sections.

Even more importantly, we decided

Editors could trade slots. If the Opinions editor had a study group at 9 pm, he could trade his slot to the Features editor.

And if you missed your slot, you went to the back of the queue

The bottleneck disappeared.

< 3 > Cheat like hell. In part we never got the paper out by midnight because nobody believed we could get it out by midnight. Most days production started around 5 pm because people had classes and the like. But there were no classes on the day before the first issue of the semester. So I asked a couple of trusted folks to start doing the layout early in the afternoon. We could only do that once, but I wanted the staff to believe that midnight was possible, and they did.

We had a network crash the second night of production, so we didn’t get the paper to bed until about 2 in the morning. But on the third night, we got there at 12:08 am. We very quickly got into a groove of completing the paper around midnight. A few times we finished up around 10 pm.

I visited the Herald’s new, much smaller offices a couple of years ago. They use a modern content management system to publish online and only put out a print edition (for appearances sake) once a week. They don’t have the avalanche of advertising revenues that recruiting ads used to provide, so I’m sure they don’t spend $8,000 per semester on alcohol. There’s no AP printer clattering away in the corner. No flats. No wax machine. No light tables. No X-acto knives. No room for the weekend magazine staff to pass out drunk on the floor. They put out a great newspaper, but from the looks of it, they could be selling insurance.

We live in prosaic times. Prosaic times.

Thanks for coming along for the ride.

If you know one person who would enjoy this kind of thing, forward it to them.

See you next Sunday (actually quite likely before then if I think of something interesting)

— James

Probably also helps that the photographs are now all digital.

No need for the negs to be drying.

What is the timeline for the modern herald now? Still same time commitment, just in a different flavor?