Prosaic Times: LLMs forget; enterprises can’t -- three possible ways forward

Context compression and the challenge of stochastic results

Being a sardonic, paid-up member of GenX, I may grump about the state of academic history today, but Jeffrey Ding’s book Technology and the Rise of Great Powers: How Diffusion Shapes Economic Competition is excellent. Ding argues:

GenAI is a general purpose technology (GPT) that will power a Fourth Industrial Revolution, equally important to the ones catalyzed by steam power, electricity and machine tool and computing technology.

GPTs are especially important because they enable many different applications, so diffusion, which takes time, is especially important. The United States grew so quickly during the Second Industrial Revolution because it excelled at diffusion even though a lot of the base level innovation happened in Germany

We can have a great, probably unresolvable, debate about whether GenAI is a Fourth Industrial Revolution or just another phase of the Third Industrial Revolution. But the point about diffusion, the skills required for diffusion and the time that takes is important — especially in light of the questions raised in the popular press asking why GenAI hasn’t yet transformed the income statements of giant institutions.

Important technology innovations always take time and skill-building to exploit. For example, large enterprises couldn’t use cloud platforms at scale until they figured out how to do “everything-as-code” and the vendor ecosystem evolved to support this with products like cloud security posture management (CSPM) tools.

What problems will large companies have to solve to exploit GenAI at scale? There are many, but the non-deterministic nature of LLMs will be an important one that we need to solve. I think there may be a combination of three potential mechanisms: (1) Using knowledge graphs as an intermediary, (2) building agents with memory and (3) possibly adopting state-space models (SSMs) (hybrid LLM-SSM architectures) for some use cases.

Memory compression and non-deterministic results

Everyone talks about compute as the bottleneck for GenAI. But decades of scaling analysis tells us that you tend to run out of memory or I/O before you run out of CPU (or in this case GPU). How many times did you have to explain to someone that just because server utilization was 10 percent didn’t mean you could reduce the number of servers by 9/10ths?

And memory constraints make the returns from LLM prompts non-deterministic. Great for writing haikus. Not so great drafting a credit decision memo — or automating most corporate processes.

LLMs apply lossy compression to context. Storing uncompressed (or even losslessly compressed) full text would be computationally impossible. A model would need to store every token, preserve pairwise relationships and update with every token. Compute increases quadratically and memory usage explodes. From what I understand:

If you feed a model 128Kb of raw text that’s about 32,000 tokens

32,000 tokens x 8,192 d-model size x 2 bytes x (Key + Value) = 1Gb per layer

1Gb per layer x 80 layers = 80Gb

And that 80Gb might get compressed down to a few hundred kilobytes

The model throws away information constantly, keeping those pieces of information that helped it reduce prediction error training. Take the sentence: “It was nearly 8 am so I put my new laptop in my old briefcase and went downstairs to the coffee shop”

The model keeps (as they are highly predictive): temporal set up, the agent and action chain, key objects like the laptop, the destination

Compression discards: exact phrasing, non-essential adjectives, narrator motivation

In short, the keeps the narrative backbone (actor → action → objects → destination → sequence) and discards the cosmetic texture (phrasing, adjectives, incidental specifics)

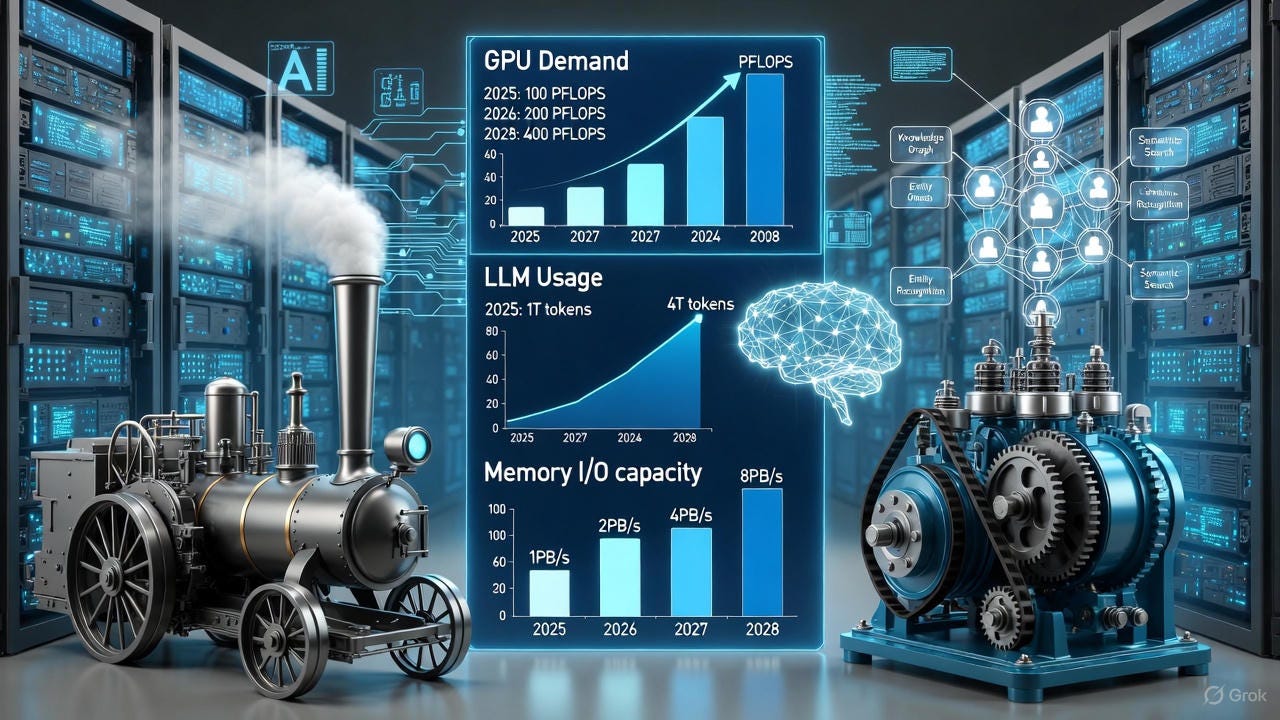

Better processors are unlikely to help here, memory bandwidth is improving much more slowly than compute efficiency or context requirements.

Context window per user/session has been increasing 30x per year

Aggregate LLM usage (number of sessions) has been growing at 10x per year (or more quickly depending on who is counting)

Compute efficiency (per GPU) has increasing 2x per year, with algorithmic efficiency doubling every eight months

Memory I/O unit capacity is growing about 50 percent per year, but may be increasing

This has all sorts of implications for our experience in using LLMs. Models forget context earlier than users expect. Small prompt can dramatically change output. Results are probabilistic. Long reasoning changes break down, and multi-step instructions degrade.

All of this makes it harder to rely on LLMs for exact data recall in enterprise settings. But if you could access large swaths of memory with confidence. You could build:

Customer service agents who could keep everything about a customer in memory

Fully autonomous document heavy workflows – with redlines and dependencies tracked across multiple, related contracts – and the ability to reason across multiple documents

Long-running agent workflows with persistent project memory (e.g. remembering every step taken and the rationale)

So what might be the solution here?

1. Knowledge graphs as an intermediary

People in McKinsey like to tease me about my fascination with knowledge graphs, but they are fascinating. When I started to read about knowledge graphs, I had the same reaction as when I first started to read about SQL and data normalization — what a intriguing way to think about information, and therefore about the world. (Yes, I’m very popular at cocktail parties.)

Knowledge graphs organize information into nodes and edges that connect nodes. Some types of knowledge graphs allow you to attach descriptive labels to edges or nodes. Each of us is a node in the knowledge graph, with edges for each of the connections between us. Here’s what’s interesting about a knowledge graph:

You don’t have to figure out the entire schema before you build the database

You can connect multiple disparate datasets more easily

You can understand complicated relationships more easily

You can perform recursive search, so you can trace dependencies more easily (e.g. vendors of vendors if you are trying to assess nth party supply chain risk)

And you can use the interrogative power of GenAI combined with knowledge graphs to unlock the “frozen data” stored away in documents in an enterprise. For example, a company could:

Build an ontology describing a business domain (e.g. claims management)

Ingest a massive volume documents describing claims (or underwriting or B2B sales) interactions — and convert semi-structured text into structured that it can use to populate a knowledge graph

Use Text-to-Cypher (which generates queries on the knowledge graph based on an English language prompt) to answer questions like: “What types of customer interactions tend to lead to out-of-profile underwriting decisions?”

When companies have used this type of pattern they have experienced fewer hallucinations and more reliable results (in part because you spot check data to validate it as you populate the graph.)

2. Giving agents memory

Using knowledge graphs as an intermediary is a powerful pattern, but also one not applicable to every use case. Agent memory can turn lossy compression into selective retrieval, increasing confidence with data recall and longer reasoning chains. One financial institution I know of is creating memory structures that many of its agents will be able to call upon.

There is real nuance here. Agents will need access to short-term memory, related to an individual interaction, segmented but long-term memory about a clients customer relationship history and more general but long-term memory that allows the agent to capture experiences and learn over time. You want a lawyer or financial advisor to learn from his or her entire history serving clients but not disclose information from one client to another — and you’d want the same from an agent that handles sensitive data and important interactions.

None of this is simple — yet. Engineers building agents that use memory need to determine what to store, how to store it, how to segment the memory and how to retrieve it. Over time, platforms will abstract away more of the technical details and reduce the implementation complexity.

3. Using state-space models

SSMs keep a compact, hidden state that gets updated one token at a time. The aspiration is to process long sequences in such a way that compute and memory requirements can scale in a linear relationship to tokens. So far though, SSMs have lagged LLMs in many benchmarks for in-context recall and complex reasoning.

The Mamba project is different from earlier SSMs because it employs selected state updates and hardware-aware design. In tests, it appears to deliver similar performance to transformer-based architectures that were twice the size.

But SSMs have limitations of their own especially in storing unique pieces of data — Mamba uses a selective state space mechanism to decide what to remember. It might not decide to remember a critical piece of information. The Jamba and TransMamba architectures propose to address this problem by combining SSM layers and LLMs layers into a single model.

Converging patterns over time

Most likely, we will see a lot of pattern convergence. Agents will both draw upon pre-populated knowledge graphs (and other databases) — and use knowledge graphs to support memory. If SSMs (or hybrid SSM-LLM architectures) get traction they will complement rather than replace LLMs, and agentic (and non-agentic) systems will draw upon multiple types of models, sometimes in the course of solving a single problem.

A reader of Ding’s might ask, what will have more aggregate impact — better models (i.e. base level innovation) or enterprises better learning how to complement models with techniques that enhance memory (i.e. diffusion and application)?

Brilliant framing around the diffusion challenge. The memory bandwith bottlenck is really the hidden constraint that nobody talks about when discussing LLM scalability. What caught me is how this mirrors the cloud adoption curve you mentioned,where enterprises couldnt scale until they figured out everything-as-code. Seems like knowledge graphs provide that same kind of structural foundation,kinda like turning implicit organizational knowledge into something queryable and reliable.

Brilliant; while diffusion's timing is critical for GenAI, ensuring equitable acces and quality education for these new skills is equally vital.